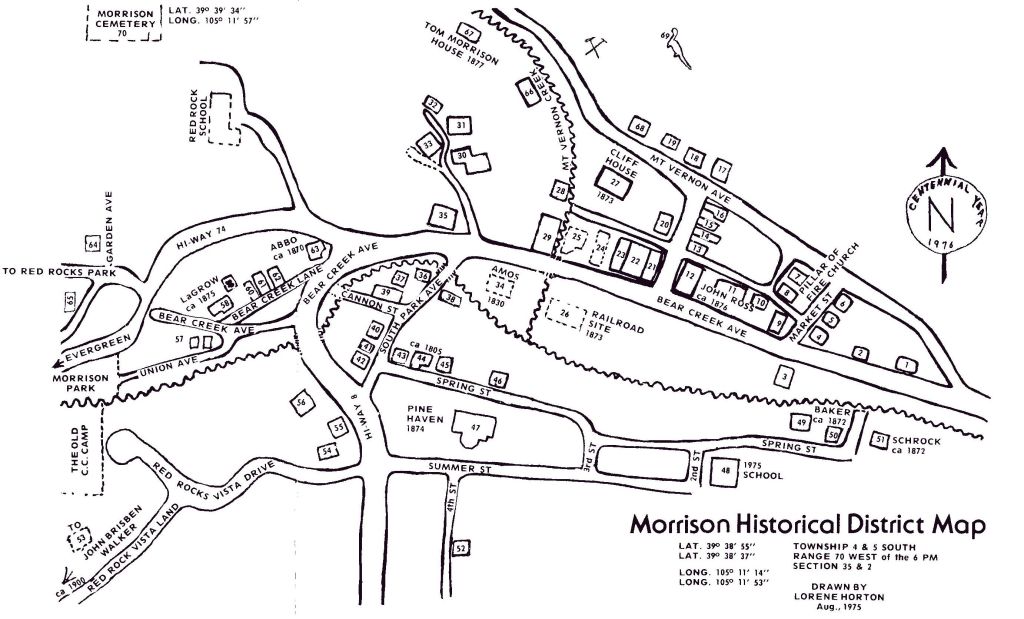

“Where is Peter Fischer’s Rock?” asked an interested descendant early in my tenure as a Morrison historian of sorts, maybe about 1996. Answering questions was a key part of the job, but this one had me stumped. I’d never even heard of Peter Fischer, though I’m confident Morrison’s earlier historian, Lorene Horton, probably had. His early arrival and many contributions to the area qualify him for “pioneer” status. Why did he seem so little known, hardly remembered?

Peter’s story as adapted and abbreviated from a summary by his great-great-granddaughter Melanie Holmberg:

Peter Fischer was born in Germany in 1826 and immigrated to Illinois in 1849 with his family (including parents, brothers, and sister). At age 33, he left the family farm in Illinois (and his wife Catherine) and moved alone to Cherry Creek in the spring of 1859, where he established a nursery business on the shores of Cherry Creek. Catherine joined him in 1860. In 1872 (before the railroad line to Morrison was completed), Peter, Catherine and 6-year-old Clara Fischer moved to Morrison, perhaps because he’d heard about the coming railroad.

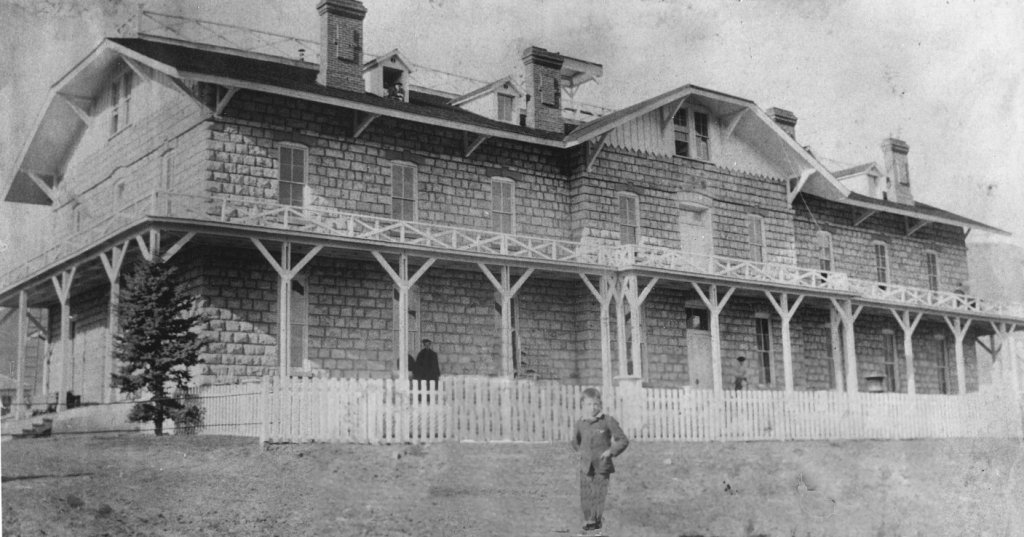

After Peter moved to Morrison he “engaged in improving his farm and experimenting on fish and is now in possession of a beautiful beer garden.”1 “Laurelei [also Lorelei] Park, near the mouth of the canon, is the favorite resort of the people of Morrison, and the surrounding country. Its proprietor, Mr. Peter Fischer, has spared neither pains or expense in fitting up a nice place for a summer resort, and seems to be reaping a rich reward for his enterprise.”2

Peter may have owned land on “Fischer’s Mountain,” aka Mt. Fischer, now Mt. Falcon. He was also the owner of Fischer’s Ditch and Flume. “Fischer’s Rock,” or “Peter’s Rock,” is the large red sandstone outcrop overlooking Morrison on which he built Fischer’s Flume “to carry water around Mt Glennon to Turkey Creek.”3 He constructed two ponds, one to serve as a swimming pool and bathing area (for which he charged admission) and a lower one to water his livestock and farm (perhaps also for the above-referenced fishery).

After his daughter’s move to Denver and his second wife’s death, Peter suffered multiple financial setbacks and failures. He eventually left Morrison for Denver, impoverished, and was living in a “county home.” He apparently didn’t have a close (or any) relationship with his daughter and grandchildren. At his death, in 1900, he was reported to have dementia.

The story of the Fischer family is, of course, far more complex than this overview. Although Clara was the Fischers’ only surviving child, her marriage to Sabatino Tovani (another story) resulted in six children and an array of descendants.

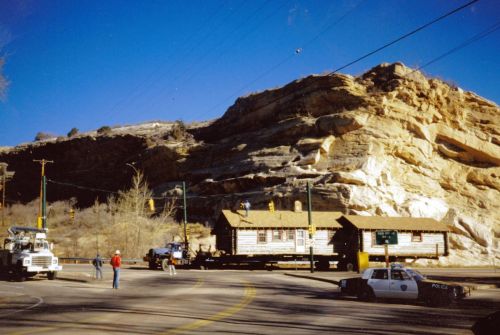

The flume was short-lived and was therefore sometimes known as “Fischer’s Folly.” Evidence of its presence remains in faint traces on the landscape (see photo below).

Sources:

1 “Morrison Matters: A Word or Two About This Enterprising Foot-Hill Hamlet. Her Business, Agricultural and Grazing Facilities Commented On.” The Rocky Mountain News (Daily), Volume 25, April 27, 1884.

2 “Lively Morrison: A Rough Sunday’s Work—A Man Kicked to Death on Sunday—Notes of Business Progress and Social Gossip.” The Colorado Transcript, July 20, 1881

3 Kowald, Francis. “A Brief Historical Sketch and Some Reminiscences of The Sacred Heart College,” typed manuscript, circa 1935, housed in Archives and Special Collections, Regis University.